Why the Duxbury calculation should be a starting point, not the answer, for separating couples

When it comes to determining a lump sum payout on divorce, the Duxbury calculation is a common place to start – but it has limitations. Find out more in this useful guide.

When clients separate, cashflow modelling can be a useful tool to consider the impact of any asset split both now and in the future.

One question that professionals regularly ask me is: “What assumptions should we make when undertaking a cashflow model?”

Making the right assumptions is key to a good outcome. As the saying goes: “garbage in, garbage out”. Without accurate or realistic assumptions, the results of any cashflow analysis are likely to be wide of the mark.

When it comes to making assumptions, the Duxbury calculation – originating from Duxbury v Duxbury Fam 62 – is a common starting point.

However, there are limitations to this approach and other models you can consider – such as one from the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). Read on to find out more about the importance of making the right assumptions, and why it matters.

Duxbury helps you work out the lump sum a client needs to generate periodic payments

The Duxbury calculation tries to work out the appropriate lump sum for a financially dependent party in the place of periodic payments (such as spousal maintenance).

The calculation is designed to arrive at a lump sum figure which, if invested to achieve capital growth, could be drawn in equal instalments and would last until the end of the recipient’s life. If the calculation has been made perfectly then there would be nothing left at the exact time of death.

However, to arrive at a Duxbury calculation, several assumptions need to be made. These will include:

- Rates of growth

- Life expectancy

- Rates of inflation.

Let’s now look at the Duxbury assumptions.

Duxbury should be used as a starting point

Duxbury tables are frequently used to estimate the capital amount required to provide a certain level of income for the rest of an individual’s life.

My view is that, while useful, the Duxbury calculation should be used as a starting point, rather than a set answer.

Of course, the accuracy of any outcome lives or dies by the assumptions the calculations are based on. And, when you generate a “number”, the client will often believe they have enough money for the rest of their life – when this may not be the case.

As a reminder, here are the assumptions Duxbury is based on:

- An income yield of 3%

- Annual capital growth of 3.75%

- An inflation rate of 3%

- The client receives a full State Pension that rises in line with the cost of living

- A consistent rate of Income Tax and Capital Gains Tax with tax bands and allowances index-linked

- A constant level of drawdown, index-linked

- The recipient lives to the exact assumed life expectancy

- There is no change to the State Pension Age in the period under review.

Duxbury also assumes there is no consideration given to ongoing product or adviser costs.

The life expectancy assumption might significantly underestimate a client’s life span

The aim of a Duxbury calculation is to ensure the lump sum generates an income for life.

However, few clients are “average”. The likelihood is:

- A client is healthy and lives to a grand old age

- A client suffers from poor health and dies before the “average”

Naturally, this is a problem for healthy clients who outlive a settlement that assumes an earlier death. So, it may be necessary to assume a longer life expectancy – and this will, of course, require a larger lump sum under a Duxbury calculation.

The client may not receive a full State Pension, and the age may rise

Duxbury assumes that:

- The client receives a full State Pension that rises in line with the cost of living

- There is no change to the State Pension Age in the period under review.

In reality, now pensions are calculated on an individual accrual basis, many individuals will not have the 35 years of National Insurance contributions required to receive the full State Pension.

Moreover, the State Pension Age is almost always under review, and highly likely to rise in the decades an individual may live.

“Cautious” investments will likely not achieve the growth needed for a Duxbury calculation

Using the Duxbury income yield and capital growth assumptions, a client needs to achieve a post-tax return of 6.75%. Assuming a static inflation assumption of 3%, this will provide a return of 3.75% above inflation.

Duxbury suggests this is achievable with a cautious investment strategy – although “cautious” is another term that means different things to different people.

Under Financial Conduct Authority rules, the maximum rate of return for a medium-risk investment cannot exceed 4.5% a year (5% a year for a tax-efficient investment).

Consequently, it’s highly unlikely that a cautious/low-risk investment strategy would generate a return of 6.75%.

In addition, investing in funds carries various fees and costs, such as fund management, adviser, and platform charges. These costs will vary significantly depending on the funds and the adviser but could easily be 1-2% a year.

The conclusion is this: lower-risk investments won’t achieve the level of returns a Duxbury calculation relies on – especially if you consider tax, charges, and inflation.

Compare this to the FCA assumption, which is:

- Investment growth 4%

- Ongoing fees 1.5%

- A uniform rate of inflation of 3%.

This represents a lower assumption than Duxbury – 1% above inflation compared to 3.75% above inflation. While likely more achievable, lower growth assumptions mean that the lump sum needed to provide a regular income will be larger than under a Duxbury calculation.

At the Resolution Financial Planning on Separation conference, I spoke about everything I have mentioned above and also modelled the difference using cash flow modelling.

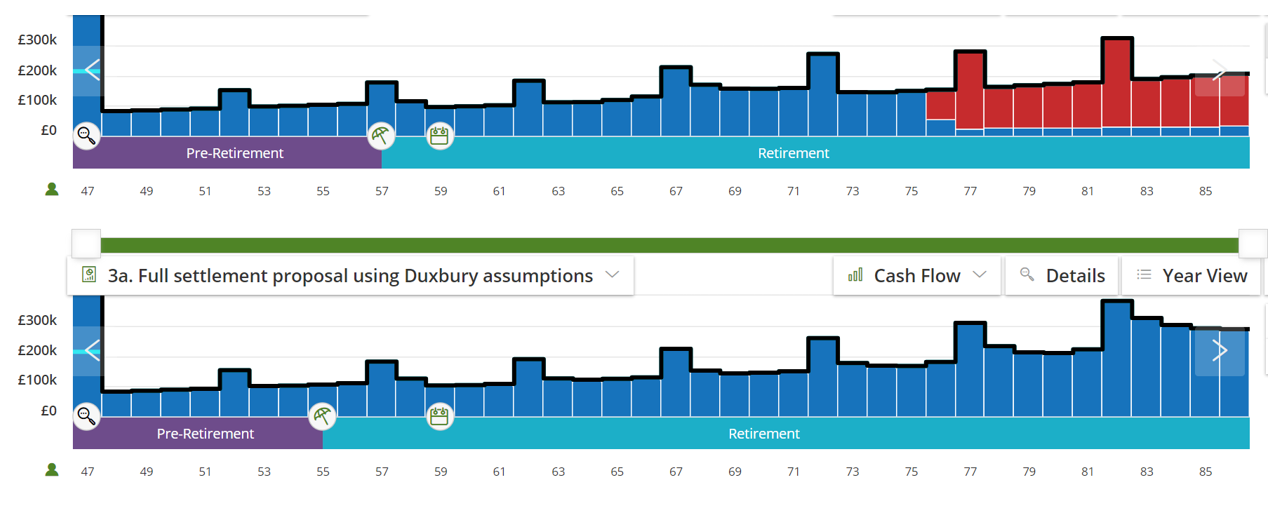

As you can see below, using FCA assumptions (top graph), the client has a shortfall (shown in red) from age 76. However, using Duxbury assumptions (bottom graph), she does not have a shortfall at all. Here lies the problem…

Expert advice can help your clients

As you have read, establishing the amount of lump sum that will generate the periodic payments a client requires can be a complex undertaking.

Of course, there could well be many different opinions concerning these assumptions, all of which could lead to very different outcomes.

I would make two points here:

- It’s important to get buy-in from all parties involved especially if working as a team. Make sure you are all in agreement before you make any calculations.

- Have reasons to back up why you suggest doing what you are doing. As with everything in the divorce financial planning world, calculations are open to interpretation. So, ensure you can back up what you are doing and why you are doing it.

If you’d benefit from professional help in this type of scenario, please get in touch. Email lottie@truefinancialdesign.co.uk or call 07824 554288.

As a new mummy, I will be on maternity leave until July 2024, so I appreciate your patience until I am back at my desk.

Please note

This article is for general information only and does not constitute advice.

The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate cashflow planning or tax planning.